“The soul

of man is not an organ but animates and exercises all the organs; it is not

a function like the power of memory, of calculation, of comparison, but uses

these as hands and feet; it is not a faculty, but a light; is not the intellect

or the will; is the vast background of our being in which they lie –

an immensity that is not possessed and cannot be possessed.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Philosopher

______________

“I consider this the best definition of this power ever given the world.

St. Paul gave a similar, more concise description of it in Acts 17:28, ‘For

in Him we live and move and have our being.’

It is the same power on which Bach, Mozart and Beethoven drew and on which

all composers are dependent if they wish to create anything worth while.

He who consciously

appropriates this inner force is inspired but technically he must be adequately

equipped to present the inspired ideas on paper convincingly.”

Max Bruch

„It is through

the Temple

of Music

we approach

Divinity.

It is here

we Experience

our true

Resurrection.“

Goethe

„Anyone

who seriously

researches Nature

must have experienced

a sense of

religious Consciousness.“

Albert Einstein

|

|

THE COMPOSER ON

THE ART

OF THE FEMININE |

|

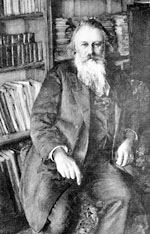

Johannes Brahms (sitting)

Johannes Brahms (sitting)

and Joseph Joachim

Johannes Brahms

in discussion with the famous violinist

and friend

Joseph Joachim

“All this is most fascinating, Johannes, and I understand now why you have always

been so aloof in this respect, even with me. We are now treading on holy

ground. But if you feel that Bach, Mozart and Beethoven were more inspired

than you were, what do you think of me?

As a young man, I, too, composed, but since associating with you so intimately,

I have long since given it up; your inspirations were of a so much higher

order than mine, your workmanship also, that further effort on my part seemed

futile.

My compositions, even my Hungarian Concerto, are being more and more neglected

and will soon be forgotten, while yours are gaining in recognition from

year to year.”

“That is true, Joseph, but it will be another half century before I shall find

my true place in the musical scheme. It is difficult, if not impossible,

to explain why one composer is more inspired than another, but I can put

my finger on one weak spot in your past, Joseph – too many official

positions and posts of honour. You are the director of the Berlin Royal

High School, you are in great demand as a violin soloist and as a quartet

player, you devote a great deal of your time to teaching; the many conferences

connected with your posts of honour encroach upon your time; you are flooded

with manuscripts of composers for violin who seek your advice – to mention only a few of the troublesome and annoying inconveniences which

have come within the scope of my own observations. All these things interfer

with composing.

A composer who wishes to write worth-while music must devote his whole time

and energy to that one occupation. If I had had as many calls upon me as

you have had, Joseph, I could not have created anything worth listening

to, either.”

“Granted, Johannes, but when we first met as young men, I was not burdened with all

of those opressing loads; I had the creative urge, too, and yet the difference

between your productions and mine were like day and night. No, there is

a deeper reason. No doubt it is natural aptitude. It must have been very

easy for Jesus of Nazareth to contact Omnipo-tence, just as it was for Beethoven;

his ideas must have come with no conscious effort on his part, as witness

the hundreds of wonderful themes in which his works abound.”

“True, Joseph, but his sketch books prove that he too toiled incessantly in order

to leave to posterity such masterpieces as the Eroica, the fifth, seventh

and ninth symphonies, the fourth and fifth piano concertos and the violin

concerto. That is why I have always taken him as my ideal; he had not only

the highest inspiration but also supreme craftsmanship.”

The famous Violinist

The famous Violinist

Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim about

Johannes Brahms

“To one

who knows him as well as I do, that is easily explained.

In spite of his crusty manner, Brahms is in reality a kindhearted man.

I have found that out in many ways. He realizes that for future generations

of composers, it would be of great value to have such detailed accounts

of his own experiences when in those trance-like states in which his inspi

rations came to him.

Those secrets

would have been invaluable to me as a young man. I also, through my early

associations with Mendelssohn and Schumann, before I met Brahms, had ambitions

to be a great composer; and if I had known then what I learned that last

evening with him, I might have accomplished a great deal more than I did.

Yes, I am convinced that he knows that young composers of the future will

profit by his revelations concerning those higher spiritual laws. He himself

gained very valuable information from the teachings of Jesus and of the

great poets.”

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

“You see, the powers from

which all truly great composers like Mozart, Schubert, Bach and Beethoven

drew their inspirations is the same power that enabled Jesus to work His

miracles. We call it God, Omnipotence, Divinity, the Creator, etc. Schubert

called it, ‘die Allmacht’ but, ‘what’s in a name?’

as Shakespeare so aptly questions.

It is

the power that created our earth and the whole universe, including you and

me, and that great Godintoxicated Nazarene taught us that we can appro

priate it for our own upbuilding right here and now and also earn Eternal

Life.

According to Jesus’ own words, He was in that case not the great exception, but

the great example for us to emulate. We are all sons of God, for we could

not have come from any other source. The vast difference, however, between

Him and us ordinary mortals is that He had appropriated more of divinity

than the rest of us.

Of course,

to the disciples it appeared that Jesus was walking on the water, but in

reality He was walking in the air. His spiritual power was so great that

He could, by drawing on Omnipotence, rise superior to the Law of Gravitation.

We call that a supernatural power but supernormal would be a better term.

Jesus was using a higher law of which his disciples in the boat were all

ignorant, and their only explanation of the phenomenon was that He had supernatural

powers, being God Himself personified. Nevertheless, their terror was very

great for we read in Matthew 14:26, ‘And they cried out for fear’”.

Brahms

“How different life on this earth would be if we could all consciously appropriate

Omnipo-tence as Jesus did.”

Joseph Joachim

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

“My belief in our immortality is based chiefly on the unde-niable fact

that all peoples of all times and all climes have always clung to the belief

in a life beyond the grave; that is to say, the more spiritually advanced

leaders of such peoples.

There are, of course, always some who do not believe in a hereafter but

that is of no importance; the fact that so many different, widely sepa

rated races of antiquity did believe it, is to my way of thinking, proof

that it is implanted in the human breast by the Creator.

By burying

with their dead weapons, articles of clothing, and various utensils which

they had in daily use, they beleived that the dead would need them in the

next world. Ancient sepulchers and the many different modes of disposal

of the dead, reveal to us the hope which long since vanished civilizations

held of a future life.

One of the

most wonderful illustrations of the universality of the belief in another

life is to be found in your American Indians, who were wholly segregated

from all the rest of mankind, and yet they talked of the Great Spirit and

the Happy Hunting Grounds where they would hunt after leaving this world.

Their idea of heaven was a primitive one, to be sure, but one finds that

the conceptions of that abode were always coloured by the state of civilization

of the nations that believed in hereafter. However, all that is unimportant;

what counts is the universality of that belief in a future life.

In the Holy

Writ it says in John 14, 10: ‘The father that dwelleth in me, he doeth

the works’.

The real genius draws on the Infinite Source of Wisdom and Power as Milton

and Beethoven did.

That is, in my opinion, the best definition of genius. Jesus was the world’s

supreme spiritual genius, and He was conscious of appro-priating the only

true source of power as no one else ever was, although Beethoven and Milton

realized too they were tapping that same source in a lesser degree.

It is all a question of degree.”

Brahms

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

“I always had a definite

pur-pose in view, before invoking the Muse and entering into such a mood.

Then when I felt those higher Cosmic vibrations, I knew that I was in touch

with the same Power that inspired those great poets and also Bach, Mozart

and Beethoven. Then the ideas which I was consciously seeking flowed in

upon me with such force and speed, that I could only grasp and hold a few

of them; I never was able to jot them all down; they came in instantaneous

flashes and quickly faded away again, unless I fixed them on paper.

The themes

that will endure in my compositions all come to me in this way. It has always

been such a wonderful ex-perience, that I never before could induce myself

to talk about it – even to you, Joseph.

I felt that

I was, for the moment, in tune with the Infinite, and there is no thrill

like it. I can understand why the great Nazarene attached so little importance

to his life. He must have been in much closer rapport with the infinite

force of the Universe, than any poet or composer ever was, and He no doubt

had glimpses of that next plane, He called ‘heaven’.

Shakespeare’s admonition ‘To thine own self be true’ has

always been one of my guiding principles.”

Brahms

Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

“..

but no matter how clever the workmanship, no composition will live unless

it is inspired.

Composing is a procedure that is not so readily explained.

When the inspiration comes, it is something of so subtle, tenuous, will-o-the-wisp-like

nature that it almost defies definition.

When in my most inspired moods, I have definite compelling visions, involving

a higher selfhood. I feel at such moments that I am tapping the source of

infinite and eternal energy from which you and I and all things proceed.

Religion calls it God.”

“It is of the utmost importance to put the thoughts on paper immediately lest

they quickly fade away. Once fixed I often look at them again and this conjures

up the same frame of mind that gave birth to them; thus the ideas grow and

expand. I am a firm believer in the germination of the idea.

I realize that the ability to have such ideas register in my consciousness

is a Divine gift.

It is a mandate from God, a charge entrusted to my keeping, and I feel that

my highest duty is to make the most of this gift – to grow and expand.

I was, however,

definitely conscious of being aided by a more than earthly Power, and that

it was responsive to my determined suggestions.

A firm believe in this Power must precede the ability to draw on it purposefully

and intelligently. That much I definitely know.”

Richard Strauss

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

“I begin by appealing

directly to my Maker. Immediately after that I feel vibrations that thrill

my whole being.

These are the Spirit illuminating the soulpower within, and in this exalted

state, I see clearly what is obscure in my ordinary moods; then I feel capable

of drawing inspiration from above, as Beethoven did. Above all, I realize

at such moments the tremendous significance of Jesus’ supreme revelation,

‘I and my Father are one.’ Those vibrations assume the forms of

distinct mental images, after I have formulated my desire and resolve in

regard to what I want – namely, to be inspired so that I can compose

something that will uplift and benefit humanity – something of permanent

value.

Straightway the ideas flow in upon me, directly from God, and not only do I see distinct

themes in my mind’s eye, but they are clothed in the right forms, harmonies

and orchestration.

Measure by measure the finished product is revealed to me.”

Brahms

|

| |

CLASSIC-Life: Herr Hübner, you have created quite a number of pieces of work, which have

the title “The Art of the Feminine”. 16 of these have the subtitle

“Love”, and 16 further ones the title “Harmony”.

When you listen

to them, you notice that they are all related to each other. Can you tell

us something about this?

PETER HÜBNER: Yes, “Femininity” first of all is a delicate topic – during

a time in which, especially in high positions, more and more women effectively

stand up for themselves.

Like the whole of nature, the microcosm of music presents us creative powers, conserving powers, and destructive powers.

In the advanced civilisations of mankind the principles of “preservation”

were attributed to the feminine element, and “creating” and “destroying”

to the masculine.

I have transferred the principles of conservation from the microcosm of music

to the compositional, and used it in a fugue of up to five parts.

The fugue theme

can be frequently modified, without encroaching on the musical element of

femininity in any way.

In this respect,

the 16 pieces of work are modifications of the very same feminine themes.

Therefore, they differ from each other. It would require too much explaining

to go into this in more detail – you can hear it all anyway.

But there is also a special story behind this: all 16 pieces of work in a series

are related to each other. One would think that it would be easy to memorise

them, and musicians might assume that they would be able to play them from

memory after a short time.

But that is made especially difficult because of the close relationship of

these pieces – if not even rendered impossible

I therefore believe that a conductor, for instance, when he knows them all,

couldn’t conduct these pieces from memory – whilst he could easily

do so if he only knew one of them.

CLASSIC-Life: Among the “Art of the Feminine” there are the two cycles “Love”

and “Harmony”. In what way do they differ?

PETER HÜBNER: Regarding the 5 polyphone voices,

the particular individual movements are the same. But the series “Harmony”

also has the basso continuo, which reveals the natural harmonious development

– whereby this basso continuo is missing in the “Love” series.

Why these two groups

“Love” and “Harmony”? Here, I must explain in more detail.

Imagine five children who are playing with each other in a meadow. The ideal

natural harmonious contact of these five children is shown in the series “Love”,

the children being symbolised by five voices.

But the basis of a natural harmonious musical development can only be the basso

continuo – which is indeed not played here, but to which the voices are

directed. In the series “Harmony” this basso continuo is played,

and it embodies the mother.

Whilst in the series “Love” we experience the children’s play only

with the mother’s omnipresence, in the series “Harmony” we

experience the mother who is creating harmony in the basso continuo, and then

only recognise unambiguously in her the basis for the natural harmonious development

of the children’s play – the 5 voices.

The interesting

thing in “Love” is that in your subconscious – and the music

expert perhaps also consciously – with the help of the children’s

play: the 5 voices – you add the natural harmonious role of the mother

in the basso continuo, sometimes though making a mistake. But you only notice

this, when you later hear the corresponding piece of work with the corresponding

number from the series “Harmony” with the basso continuo, i.e.

with the role of the mother.

In natural harmonious

music, the basso continuo always determines the natural harmonious development,

and so the basso continuo determines here also the natural harmonious development

of the 5 voices – just as the mother determines the natural harmonious

development of her five children.

As this is about “The Art of the Feminine”, besides the mother,

the five voices represent five girls.

In “The Art of the Masculine” the father will correspondingly play

the decisive harmonising part as the basso continuo, and the children playing

are sons.

But the matter is even more specific: In the first 4 “Meditations” there

are not five different girls, but a girl playing by herself simultaneously

in 5 parts. Musically it is about a theme that is set up to fivefold in playing

musical motion within itselfintellectually guided and maintained by the

mother as a basso continuo in the series “Love”, and physically

and/or tonally in the series “Harmony”.

Thus, in “Love”

the mother is only present in the mind, and only determines the natural, harmonious

fivefold dance of the girl through her mental presence, and in “Harmony”

the mother is physically and/or tonally present, and in the basso continuo

we experience the natural basis of the harmony of the fivefold dance.

So far the “Meditations”

1-4 in “Love” and/or “Harmony”.

In the “Meditations” 5-8 we are concerned with the fivefold dance

of two girls. In the meditations 9-12 there is the fivefold dance of three

girls, and in 13-16 the fivefold dance of four girls.

The mother of all

four girls is one and the same – which you can gather from the development

of the basso continuo. And which of the girls is just dancing and in how many

parts at the same time, can be gathered from the themes you are hearing.

In an extended form, the “Metamorphoses” have developed from these

two cycles “Love” and “Harmony” – whereby the or

chestra was enlarged, as further motifs were added: new people of the musical

action and/or dance – girls and boys.

Now somebody might

ask: Why is he doing all this? Here, he is producing a number of musical pieces

with 5 voices in “Love”.

Then, he adds the basso continuo in a further series “Harmony”.

And finally in “Metamorphoses”, he brings in more musical themes

and motifs.

In “Metamorphoses”

I have included everything. So why would I want ”Harmony” and “Love”

as well?

Here we might have

the view of the music producer thinking of the economic aspect and/or the

music consumer, who thinks in terms of the laws of economicalness. The matter

has a different background.

Every person must learn to deal with himself harmoniously. Almost everybody

is aware of the fact that this is not easy and by no means always easy.

In “Love”

you, as the listener, can learn or get used to handling yourself simultaneously

in an up to fivefold way – harmoniously!

So you can learn to play 5 different parts simultaneously within yourself,

without facing dissonant and/or disharmonious collisions, but on the contrary

in a sensible togetherness – which is audibly proven by the music of

5 voices as a whole.

Where do you nowadays

find such a teaching and learning process? At home, in a nursery school, at

school, at university, in your job?

Such natural harmonious dealings with yourself is the pre-condition for natural

harmonious dealings with other people.

In the “Meditations” 5-8 – as I have already explained –

we are concerned with the fivefold natural harmonious dealings of two sisters

with themselves, and up to 5 x 5 = 25 fold with each other.

Thus, the learning

process is on the one hand the repetition of the fivefold dealings with yourself,

as learned in the “Meditations” 1-4. But in addition, we now have

the natural harmonious dealings with the sister, who at the same time handles

herself in a fivefold way. Correspondingly, the educational scale is extended

to No. 16.

In the series “Harmony”,

the knowledge is included that the same natural and inevitable laws of harmony

determine all our inner lives: two or several people deal with themselves

as well as each other according to the same harmonious laws.

The “Metamorphoses” extend this individual and social educational

process, and in addition, lift it into the ecological area. With the joining

orchestra voices, the individual, the social community and thereby related

and non-related people, and finally also the ecological conditions are integrated

into the harmonious play, according to the same laws of harmony.

Out of this “whole”

nobody would be able to hear with certainty the harmonious togetherness of

two or several people as well as the laws according to which this togetherness

develops in the “Metamorphoses”, if there wasn’t also “The

Art of the Feminine” the two groups “Love” and “Harmony”

in the cycle.

For the listener

is too much distracted by the additional voices of the orchestra in the “Metamorphoses”,

to clearly hear the fivefold conversation of an individual girl with herself,

or the part of the mother.

For this reason, it was and is necessary to record all three orders in a separate

form. That is classical music: Education for the soul, as Socrates calls it.

CLASSIC-Life: Herr Hübner, at your request, the picture of Maria was put on the CDs of

“Art of the Feminine”. Do you regard her as a special personification

of femininity?

PETER HÜBNER: When I first saw this portrait of the Pieta in St Peter’s Cathedral in

Rome – that was in 1972, I spent about half a year near Rome, and travelled

quite regularly into town – I was deeply impressed by this work of Michelangelo.

You have to imagine: a mother has just seen her son murdered – the worst

that could ever happen to her.

We are used to women

turning hysterical, when they lose their handbags or their husbands stray.

The average citizen all over the world would expect a women who has just lost

her son, to be absolutely care-worn, and this to be expressed on her face.

No sign of all that in Mary, as portrayed by Michelangelo.

And if you then

look at her son in her arms, then you probably first notice the crown of thorns

and the serious wounds, but finally you see the face of a very alert, absolutely

relaxed man resting in his mother’s arms.

For me, the Jesus in this portray was more alert and more present than most

of the people who were wandering around St Peter’s Cathedral. He seemed

to be simply resting thoroughly and relaxing.

What I also noticed

was that he was much bigger than his mother, and that he seemed heavy –

but nevertheless she was holding him without any effort in her arms, as if

he had no weight at all.

This portrait of

mother and son made me think hard. Obviously Michelangelo had managed to present

him as an immortal soul: wide awake, resting deeply, completely relaxed, full

of life, and despite the outer wounds and the crown of thorns on his head

also completely without pain.

And obviously his mother saw him like that, too, and was neither blinded by

wounds nor death nor weight.

That is why she

wasn’t suffering. This Mary was obviously living beyond birth and death,

and recognised her son as being immortal. And she wasn’t older than her

son, either.

Most men think, when they father a child, that they are the creator of this

child and that is why the child is to bear their name. In my opinion, women

are a little more restrained in this respect.

When somebody is

the creator of something, he usually knows what he is the creator of –

at least that is what one would think.

But the men who are fathering a child do not know of what they are the creator,

although they think they are the father, and also say that they are. They

don’t even know if it will be a boy or a girl – never mind the rest.

But then who is

the creator of this child? Somebody must be the creator and know what he is

creating. I have the impression that Michelangelo knew and expressed a lot

more of this than most people would guess.

A mother giving birth to an immortal child, a son who was murdered, but lives,

who – although physically existing – is absolutely without weight

for his mother: that shows me a vision of life’s reality which in many

ways does justice to superior ideals. For this reason, I asked – when

we are dealing with ideal femininity – to use this picture of Mary.

This reality –

as Michelangelo expressed in his Pieta – I also tried to express in the

“Hymns of the Domes”, whereby the slightly louder intermediate parts

also remind of such ignorant views of people who in their narrow-minded limited

understanding of creation imagine that it was possible to kill Christ and

thereby harm his mother.

The name “Mary”

is also interesting, because originally it meant “cosmic ability to think

and universal creativity”, and the person who extends his thinking, can

hear this name more and more clearly in his inner being.

I hope the “Art

of the Feminine” and the “Hymns of the Domes” do justice to

the claim and the view of Michelangelo.

The central themes in “Hymns of the Domes” come from the “Art

of the Feminine”. Thus, I have arranged the “Art of the Feminine”

for the organ, and I have called these arrangements “Voice of the Domes”.

It is interesting

that we have the same view of the world and/or of life as we find with Michelangelo,

and probably also at least among the people in higher positions in the catholic

church – because otherwise the portrait wouldn’t be in St Peter’s

-, in the Bhagavad Gita.

Here, we have Krishna,

resting in himself, fully conscious, not active, and Arjuna, his student,

who knows his immortality. Krishna symbolises the immortal soul like Christ,

and Arjuna characterises the cosmically developed powers of cognition, which

in the end cannot be deceived by the confusion of the raging world events.

In this respect,

I see a perfect, outstanding presentation of that phenomena of yoga in Michelangelo’s

Pieta: better, more convincing, more comprehensible than I have ever seen

in a picture in Asia.

If someone asked

me to portray yoga and its principles in the best possible way, I would choose

the picture of the Pieta to do so – whereby the real understanding clearly

only develops, when you know the whole story: about the mother and the murdered

son, and the various levels of knowledge of this matter which I have already

explained – starting with the murdered son and the suffering mother to

the immortal son, and the mother who is therefore not suffering.

The path of yoga is exactly the path of ignorance to the knowledge of these

facts. I have learned yoga, I spent a long time in Asia in the Himalayas for

this purpose, and I practised yoga – in the late sixties, early fiveties

I taught thousands of people yoga, and I know what I am talking about.

In different cultures and religions there are many portrays of goddesses of

wisdom.

When I see those

pictures, I don’t know what would bring me to the conclusion this is

an expression of “wisdom”. It is not possible for me to follow the

thought, that this is a portrayal of a wise woman.

But when I see Mary, as portrayed by Michelangelo, and I know the background

story, then her unstressed, youthful appearance can only be explained in such

a way that she must be wise, because otherwise she would look bowed down with

grief, as this is indeed the case with a lot of pictures of Mary, which have

been created by ignorant artists – where her creators seriously imagine

those Romans would have been able to murder God’s son and bring disaster

on his mother.

It is surely the

most terrible thing that can happen in the world, that somebody murders a

mother’s son – there is nothing worse. But if she subsequently does

not suffer, she is either completely callous or without conscience, or she

is wise and knows about immortality. This picture of Mary has an extremely

meditative effect – it is worthwhile having a look at her, closing your

eyes and doing a bit of soul-searching, internalising it and learning to regard

the world with the eyes of this woman.

That is why I also

recommended that picture of Mary to the publisher’s for the label „Peace

of Mind“ regarding spiritual music.

|

|